Madrid, Spain

November 2, 2016

Investigadores de la UPM utilizan un equipo multi-robot para medir las variables ambientales de los invernaderos y permitir el control constante de las condiciones de los cultivos.

Investigadores del Grupo de Robótica y Cibernética (RobCib) del Centro de Automática y Robótica (CAR) -un centro mixto de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) y del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC)- han empleado un equipo formado por un robot terrestre y otro aéreo para medir la temperatura, la humedad, la luminosidad y la concentración de dióxido de carbono de un invernadero, tanto en el suelo como en diferentes alturas. La información que recogen ambos robots sobre el invernadero permite conocer en todo momento las condiciones de los cultivos y detectar problemas antes de que sea demasiado tarde.

Equipo de robots empleado en los experimentos. / CAR (UPM-CSIC).

¿Qué hacen esos robots que se mueven entre las plantas? Esta es una pregunta que en un futuro próximo se podrá hacer la gente que visite un invernadero. Lo cierto es que la productividad de estas explotaciones depende en gran medida de las condiciones en las que crecen las plantas. Mantener la temperatura, la humedad y otras variables en valores adecuados permite obtener buenas cosechas en términos de cantidad y calidad. Sin embargo, cualquier desequilibrio en estas variables puede causar estragos que van desde la caída de la productividad hasta la pérdida de la cosecha. Por esta razón es importante conocer al momento y de forma continua las condiciones del invernadero. Volviendo a la pregunta inicial, estos robots están haciendo un trabajo que los humanos no pueden ni quieren hacer: supervisar las condiciones ambientales del invernadero durante 24 horas al día y 365 días al año.

¿Por qué utilizar varios robots en lugar de uno solo? Básicamente porque la unión hace la fuerza. No es solo que dos robots puedan cubrir un invernadero empleando menos tiempo que uno solo, sino que cada uno puede aprovechar sus cualidades para acometer las tareas que se le dan mejor. En este caso, el robot terrestre aporta robustez, autonomía y tolerancia a fallos, ya que puede recorrer los pasillos del invernadero cargando con su compañero durante 5 horas. Por su parte, el robot aéreo aporta agilidad y velocidad, ya que es capaz de intervenir en momentos precisos, accediendo a zonas difíciles y tomando medidas a diferentes alturas. Todo esto ha sido probado con éxito en las simulaciones y trabajos de campo realizados en un invernadero experimental de la Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería Agronómica, Alimentaria y de Biosistemas de la UPM.

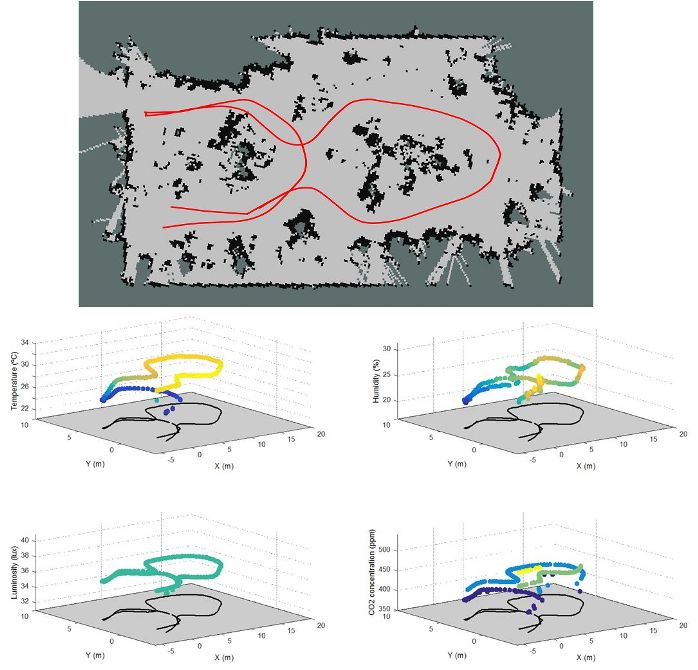

Mapa del invernadero construido por el robot terrestre y mapas de temperatura, humedad, luminosidad y CO2 realizados durante un recorrido del invernadero. / CAR (UPM-CSIC).

El estudio que ha llevado a cabo un equipo de investigadores del grupo RobCib establece una estrategia para que el equipo de robots sea capaz de cumplir con su misión. Primero, el robot terrestre recorre los pasillos del invernadero controlado con un mando para generar un mapa. A continuación, este robot realiza su ruta en el invernadero de manera autónoma y va tomando medidas de temperatura, humedad, iluminación y concentración de dióxido de carbono. Cuando el robot terrestre encuentra un obstáculo que impide su avance o detecta una medición anómala, el robot aéreo despega, realiza una ruta para evitar el obstáculo o investigar las causas de la anomalía y vuelve a aterrizar sobre el robot terrestre. Podemos ver a los robots trabajando sobre el terreno en esta grabación realizada por los investigadores.

Este trabajo, que ha sido publicado recientemente en la revista Sensors, continúa con una de las líneas de investigación del RobCib, la aplicación de robots en la agricultura bajo plásticos. Los próximos objetivos son, en opinión de los investigadores, “lograr que el equipo opere de forma continuada en un invernadero productivo y comparar su rendimiento con el de otras alternativas como las redes de sensores”. Así mismo, los principales retos tienen que ver con la autonomía del sistema formado por los robots y la navegación autónoma del robot aéreo en el invernadero. Lo que parece cada vez más cierto es que los robots se están haciendo un hueco en los invernaderos.

Enlaces de interés:

http://blogs.upm.es/robcib/2016/10/06/robotica-en-invernaderos/

ROLDAN, J.J.; GARCIA-AUNON, P.; GARZON, M.; DE LEON, J.; DEL CERRO, J.; BARRIENTOS, A. "Heterogeneous Multi-Robot System for Mapping Environmental Variables of Greenhouses". Sensors 16 (7). DOI: 10.3390/s16071018. July 2016.

Robots gain a foothold in greenhouses

Researchers from UPM use a multi-robot team to measure environmental variables of greenhouses and to ease the continuous monitoring of crop conditions.

Recently, researchers from the Robotics & Cybernetics Research Group (RobCib) at Centre for Automation and Robotics (CAR), a joint centre between Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), have used a team compound by a terrestrial robot and an aerial robot to measure temperature, humidity, luminosity and carbon dioxide concentration in the ground and at different heights. The information about the greenhouse collected by both robots allows us to know the crop conditions at any moment and to detect problems before it is too late.

What are those robots doing moving among the plants? This is a question that in a near future people will ask when visiting a greenhouse. The fact is that the productivity of these exploitations greatly depends on the conditions in which plants grow. To keep the temperature, humidity and other variables in suitable values allow us to obtain good crops in terms of quality and quantity.

However, any imbalance in these variables can cause havocs ranging from productivity fall to crop loss. For this reason, it is important to know at all moment the conditions of the greenhouse. Back to the initial question, these robots are doing a work that humans cannot perform or actually they are not willing to: supervise the environmental conditions of the greenhouse for 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Team of robots used in the testing. Credits: CAR (UPM-CSIC).

Why do we use various robots rather than just one? Basically it is because strength comes in numbers. Not only because two robots can cover a greenhouse in less time than just one, but also each robot can take advantages of their qualities to perform the tasks they do best.

In this case, the terrestrial robot provides robustness, autonomy and fault tolerance, since it can go cross the corridors of the greenhouse carrying its partner for 5 hours. Thus, the aerial robot provides agility and velocity, since it is able to operate at precise times, accessing difficult areas and taking measures at different heights. All this has been successfully tested in simulations and fieldworks carried out at an experimental greenhouse from School of Agricultural, Food and Biosystems Engineering at UPM.

The study carried out by a team of researchers from the RobCib group suggests a strategy to fulfill the mission of the team of robots. Firstly, the terrestrial robot goes through the greenhouse corridors for monitoring and mapping. Later, this robot navigates autonomously taking measurements of temperature, humidity, luminosity and carbon dioxide concentration.

Greenhouse mapping developed by the terrestrial robot and maps of temperature, humidity, luminosity and carbon dioxide concentration carried out in the greenhouse. Credit: CAR (UPM-CSIC).

When the terrestrial robot finds an obstacle that prevents its advance or detects an anomalous measurement, the aerial robot takes off and performs a route in order to a avoid such obstacle or to investigate the causes of the anomaly, and then it lands back over the terrestrial robot. We can see the robots performing their tasks on this video recorded by the researchers.

This study, which has been recently published in the Sensors Journal, continues with a research line of RobCib, which is the usage of robots in greenhouse farming. The next goals are, according to the researchers, “to achieve that the team continuously operates in a productive greenhouse and to compare its yield with other alternatives such as sensor networks”.

Likewise, the biggest challenges are related to the autonomy of the system compound by the two robots as well as the autonomous navigation of the aerial robot. It seems increasingly clear that robots are gaining a foothold in greenhouses.

ROLDAN, J.J.; GARCIA-AUNON, P.; GARZON, M.; DE LEON, J.; DEL CERRO, J.; BARRIENTOS, A. "Heterogeneous Multi-Robot System for Mapping Environmental Variables of Greenhouses". Sensors 16 (7). DOI: 10.3390/s16071018. July 2016.

Link of interest

http://blogs.upm.es/robcib/2016/10/06/robotica-en-invernaderos/