West Lafayette, Indiana, USA

March 29, 2023

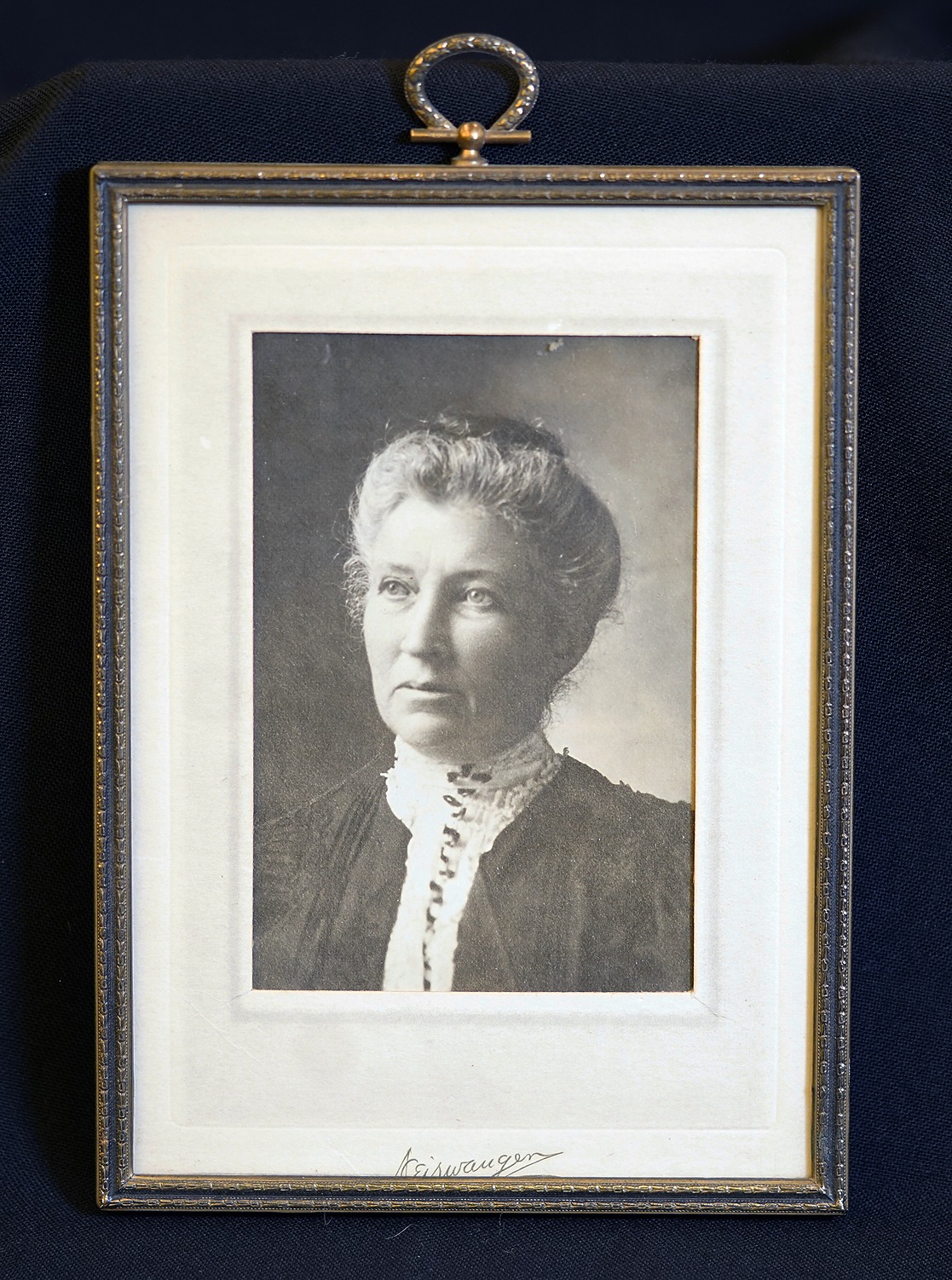

At a time when most women didn’t own land, and none had the right to vote, Virginia Meredith didn’t let anything stand in her way while becoming one of America’s leading voices for women’s role in agriculture and education.

Meredith, Purdue University’s first female trustee from 1921 to 1936 and a champion for the study of home economics across the Midwest, was the driving force behind the construction of women’s dormitories on campus, as well as for the Memorial Union on the eastern edge of campus. For as significant as her contributions were to Purdue, Meredith’s trailblazing path burned even deeper in the field of modern agriculture.

Born in 1848 on her family’s farm in Fayette County, Indiana, Meredith learned how to run a successful farming operation from her father.

Fred Whitford, clinical engagement professor of botany and plant pathology and author of The Queen of American Agriculture: A Biography of Virginia Claypool Meredith, said her early education set her on a path of lifelong success.

“Early on, her father taught her what would have typically been taught to the boys, but to him it made no difference that she was a girl,” Whitford said. “That’s the part in her story that’s extremely important to me; that she was taught from the beginning of how to raise livestock, what it was to farm and how to manage the books.”

After attending college and moving back home to her family, Meredith met and married her husband, Henry. She was widowed a few years after their nuptials, when Henry succumbed to a case of pneumonia. At the age of 34, she inherited Henry’s family farm in Cambridge City, Indiana. Meredith quickly learned the farm was bankrupt. With her exceptional cattle breeding knowledge and farm management skills, she was able to successfully pay the debts before selling the family farm to start one under her own name.

Forging a path for women in agriculture

While Meredith worked to pay off her husband’s family debt, Whitford said she also traveled across the country teaching predominantly male audiences how to profit from breeding livestock and the latest knowledge within the field of agriculture.

“Back then in the 1890’s, there was no Extension in the states. Instead, there were Farmer’s Institutes being held across the counties,” Whitford explained. “During the winter months, William Carroll Latta, a professor from Purdue’s College of Agriculture, hired speakers who would travel the country for six days a week, speaking on topics of expertise and sharing newfound knowledge and techniques prior to the growing season. It allowed those in the audience to hear from the experiences of others as well as to be taught what the research was finding.”

It was during an 1895 Farmer’s Institute lecture in Mississippi where Meredith received a medal from the state’s residents, dubbing her America’s “Queen of Agriculture,” one of the first women to be recognized for her work as a farmer.

In his research, Whitford said Meredith was known for rather radical views for that time period. In one of Whitford’s findings, Meredith was quoted as saying: “Women’s work is not discounted on account of sex. A bushel of wheat brings market price; a cow makes as many, or more pints of butter when owned by a woman as when owned by a man.”

In 1899, Meredith decided to adopt two children, Mary L. Matthews and Meredith Matthews, after a friend’s passing. Now a single mother, Meredith’s world took a dramatic turn.

“She was truly a modern woman: she had a profession, and she was also maintaining a family,” Whitford said. “Both of these things were very important to her.”

Adopting her children forced Meredith to consider the future of home economics, while also making income as a livestock breeder. Whitford said from this moment on, her Farmer’s Institute lectures took on additional topics dealing with the importance of educating women and their involvement in their communities.

Fighting for what was right, for all

While this change for Meredith came during the same timeframe as the women’s suffrage movement, she was tackling women’s rights from a different angle.

“Obviously she wanted the right to vote, but she said there was so much more that women were also needing,” Whitford said. “She was a fierce advocate for women’s education, the availability of jobs for women, the ability for women to be involved in politics and so much more.”

Meredith became a predominant writer for major trade magazines, gaining the respect of many in the industry through her opinions expressed in those articles.

By 1910, Meredith’s daughter, Mary, was living in West Lafayette, where she began as an Extension home economics instructor before becoming head of the newly founded Department of Household Economics in 1926. Meredith decided to move in with her daughter in 1916, Whitford said, likely envisioning a life of retirement. But Purdue came calling in 1921, naming her a trustee of the university.

One of her first causes, Whitford said, was the construction of adequate dormitories for female students.

“There was a women’s dorm on campus, formerly across the street from Smith Hall, but it was dilapidated and only held around 50 women. If the women weren’t local and couldn’t live at home, they were forced to live in area homes in exchange for maid and servant work,” Whitford said. “Virginia felt these women were not in safe environments, and they deserved safe and stable dormitory housing just as the men did.”

Twelve years after she was appointed trustee, Meredith saw the grand opening of the Duhme Hall, the university’s first modern female residence hall. With an increase in female students admitted, Meredith continued to fight for further housing options for females. Just after her death in 1936, the second residence hall for women, Shealy Hall, was opened, with Meredith Hall, named in her honor, opening in 1965.

While Meredith’s desire for better opportunities for women was a driving force, her patriotism ran just as deeply, overseeing the fundraising and construction of the Purdue Memorial Union.

“She never gave up on her desire to memorialize the men and women who died fighting in World War I, and she lived to see that be built,” Whitford said. “All of this was possible through her tenacity, which was really her whole life; obstacle after obstacle. It just shows that perseverance is the right word to describe her personally, because she never gave up on what was important to her.”

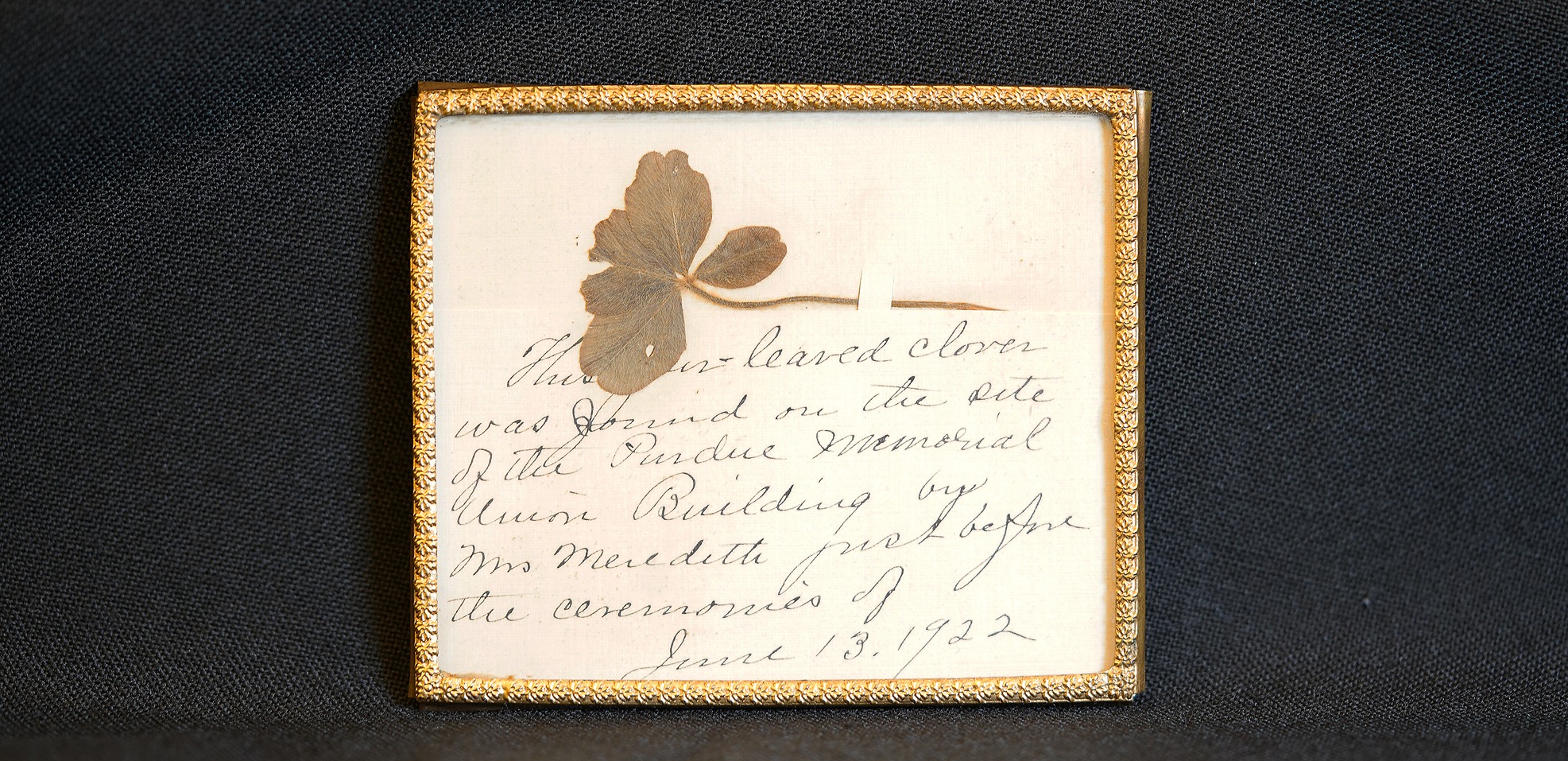

A four-leaf clover, found by Virginia Meredith during the Purdue Memorial Union's grand opening, was pressed by the former trustee in a small frame. This item, along with a few others, were donated to the Purdue Archives in December 2021 by a living relative of Meredith's.