| The

Green Revolution spreads to South Asia - Norman

Borlaug's "Kick-Off Approach"

Borlaug’s grand scheme for the campaigns was what he

called the “Kick-Off Approach,” which he based on

outright rejection of the hypothesis that agricultural

development of necessity has to be slow. His Kick-Off

Approach was founded on manipulating three

factors—technical, psychological and economic— in such a

way as to achieve rapid results. The technical factor

had already been proved to his satisfaction in the

results of the field trials. He now had to work on the

psychological and economic factors to get the required

policy changes.

Due to

drought, late sowing and poor germination, India’s

spring harvest in 1966 from approximately three thousand

hectares sown to Mexican wheat varieties, in half-acre

plots on thousands of farms, produced mixed results.

Many were good; a few were excellent. Borlaug, ever the

optimist, said, “With superb handling of supplementary

topdressing with nitrogen fertilizer and timely

application of irrigation, the seedlings tillered

profusely.” And indeed in many locations yields were

much better than any that had previously been recorded

in India. Norm said, “The Lady of Serendip had smiled

upon us, there was widespread enthusiasm, and euphoria

reigned in a few locations.”

At the

time, the drought and famine were at their worst in

northeast India, especially in Bihar and West Bengal.

Under

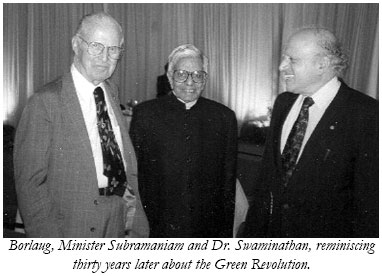

these dismal conditions, Minister of Food and

Agriculture Subramaniam made a courageous and historic

decision. Against the advice of several of his senior

scientists, he decided to import eighteen thousand tons

of the short-strawed, highyielding Lerma Rojo 64 seed

from Mexico.

About

the large import of seed, Norm says, “It unleashed a

flood of criticism, because of the risks involved, from

many academicians in ivory halls in affluent countries

from around the world. Shri Subramaniam and I were

charged by some critics with recklessly and

irresponsibly playing with the lives of millions of

people.”

In the

fall of 1966, approximately 240,000 hectares were

planted with seed of Mexican varieties. Before the

plantings were made, a great controversy developed, with

the economists from the Ministry of Agriculture, the

Planning Commission, and the Rockefeller Foundation,

including heavyweight David Hopper, on one side of the

issue and Borlaug and Glenn Anderson on the other.

Norm

recalls, “The economists insisted that we should cut

back the fertilizer application from 120-40-0 kilograms

per hectare of nutrients to 40-20-0 so that three times

more area and families could share the benefit of

fertilizer. We argued loudly and heatedly that this

scale-back in fertilizer recommendations was premature,

for we had not yet overcome the skepticism and

psychological barrier of the traditionalists, peasant

farmers, bureaucrats and senior scientists. At one

point, the debate became both emotional and heated. With

the diplomacy of Dr. Ralph Cummings, head of the

Rockefeller Foundation team in India, we finally calmed

down. We stood our ground and won the argument and the

heavy rate of fertilizer was applied on 240,000

hectares.” The dramatic results vindicated Borlaug and

Anderson. The Mexican seeds were the catalyst.

Fertilizer was the fuel. [...]

Borlaug

informed those present of the outstanding success of the

wheat campaign and the enthusiasm of the farmers for the

new wheats and the associated package of production

technology. He closed by saying that if the government

of India now would adopt an economic policy that would

stimulate the adoption of the new technology, it could

trigger a revolution in wheat production. Borlaug

informed those present of the outstanding success of the

wheat campaign and the enthusiasm of the farmers for the

new wheats and the associated package of production

technology. He closed by saying that if the government

of India now would adopt an economic policy that would

stimulate the adoption of the new technology, it could

trigger a revolution in wheat production.

Borlaug

indicated that government action was needed to assure

-

the availability of the right kind of fertilizer at

reasonable prices at the village level six weeks

before the onset of the planting season;

-

credit for the farmers to purchase fertilizer and

seed before planting, to be paid back at harvest;

and

- an

announcement before the initiation of the planting

season that, at harvest, farmers would receive a

fair price for their grain.

He said

the price should be similar to that of the international

market rather than only half that price, as had

prevailed for decades under the cheap food price

policies that had prevailed since India’s independence.

[...]

Norm

left for Mexico four hours after the meeting. Two weeks

later he received from offices of the Rockefeller and

Ford foundations in New Delhi a series of clippings

dated April 1st from all the major New Delhi newspapers.

The clippings disclosed a drastic change in policies on

fertilizer on two fronts: the government would begin to

increase fertilizer imports for the short-term and would

embark on a dynamic program to expand domestic

fertilizer production. The subsequent increases in

availability and use of fertilizer contributed to

dramatic increases in food production. |