|

Third Innovation: Changing the Wheat Plant’s

Architecture

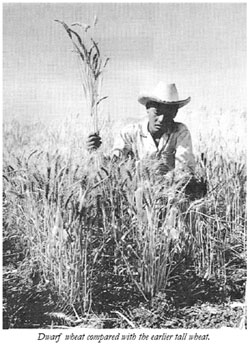

Mexico’s wheat varieties were naturally slender and

inclined to be tall. None of the varieties was capable

of efficiently using heavy applications of fertilizer to

increase yields. When fertilized they grew tall and

rank; with wind at the time of irrigation or with rain

they fell flat on the ground. Thus, more fertilizer

often meant less grain per hectare. As the use of

fertilizer increased and yields climbed to 4,500 kilos

per hectare, lodging—the tall wheat plants heavy with

grain falling over before ripening— began to limit

further increases in yields. Borlaug began a search for

wheat from different areas of the world to locate a

suitable source of genetic dwarfness to overcome this

barrier. He grew more than 20,000 lines, but found none

with short, strong stems.

In

late 1952, Dr. Orville Vogel, a prominent US Department

of Agriculture wheat breeder stationed at Washington

State University, had obtained preliminary successes in

crossing a Japanese dwarf winter-habit wheat with his

tall US winter wheats. Vogel had obtained a sample of

the Japanese dwarf wheat seed—Norin 10—from a USDA

agricultural advisor who was serving in Japan after

World War II. The advisor had sent the seeds back to the

USDA, which distributed them to several American wheat

scientists, including Vogel, in 1948. In

late 1952, Dr. Orville Vogel, a prominent US Department

of Agriculture wheat breeder stationed at Washington

State University, had obtained preliminary successes in

crossing a Japanese dwarf winter-habit wheat with his

tall US winter wheats. Vogel had obtained a sample of

the Japanese dwarf wheat seed—Norin 10—from a USDA

agricultural advisor who was serving in Japan after

World War II. The advisor had sent the seeds back to the

USDA, which distributed them to several American wheat

scientists, including Vogel, in 1948.

When

Borlaug learned about these short-strawed wheats, he

embarked on a third major innovation. In 1953, he

obtained a few seeds from Vogel’s most successful lines

and began crossing them with the most promising, broadly

adapted Mexican varieties. A new type of wheat—short and

stiff-strawed instead of tall and slender—began to

emerge. The progeny of the Japanese short wheat tillered

profusely, thrusting up more stems from the base of the

plant than western wheats, and it had more grains per

head. A series of crosses and re-crosses gave rise to a

group of so-called dwarf Mexican wheat varieties. The

potential yield of the new varieties, under ideal

conditions, increased from the previous high of 4,500

kilos per hectare to 9,000 kilos per hectare. [...]

The

dwarf Mexican wheats were first distributed in Mexico in

1961 and the best farmers began to harvest five, six,

seven, and even eight tons per hectare. Within seven

years, the national average yields had doubled. Borlaug

named two of the best strains Sonora 64 and Lerma Rojo

64. It was these same dwarf Mexican wheats derived from

the early days of Borlaug’s transformative efforts that

would later serve as catalysts to trigger the

Green Revolution in India and Pakistan.

Borlaug’s remarkable achievement in so few years was

rare. Advances in agriculture typically are gradual. In

describing the event, Don Paarlberg, who at the time was

Director of Agricultural Economics in the office of the

Secretary, US Department of Agriculture, wrote: “Several

things about this breakthrough made it special, gave

it particular significance. It came in the hungry part

of the world, not in those countries already surfeited

with agricultural output. It came in the semi-tropics,

which had long been in agricultural torpor, not in the

temperate climates, where change was already occurring

at a pace more rapid than could readily be assimilated.

It produced new knowledge and technology that could be

used by farmers in small tracts of land, rather than

being, like many technological changes, adaptable only

on large farms. And it was a breakthrough that came

voluntarily, up from the grass roots, rather than being

imposed arbitrarily from above.”

|