Greenbelt, Maryland

May 27, 2009

|

|

The

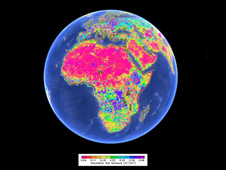

AMSR-E satellite instrument captured data over Africa on

April 7, 2004 from which this image of global root-zone

soil moisture was produced. The data overlays a Google

Earth map of the entire continent, with warmer colors of

pink, orange and yellow depicting lower levels of

moisture and cooler colors of green and blue and purple

indicating higher levels of moisture in the soil.

Credit: NASA and Google Earth |

| |

|

|

The

AMSR-E instrument delivers global soil moisture

observations to combat poor data coverage in some

regions due to sparsely located ground-based sensors

like the one in this photograph. Credit: NASA JPL |

Soil moisture is essential for

seeds to germinate and for crops to grow. But record droughts

and scorching temperatures in certain parts of the globe in

recent years have caused soil to dry up, crippling crop

production. The falling food supply in some regions has forced

prices upward, pushing staple foods out of reach for millions of

poor people.

NASA researchers are using

satellite data to deliver a kind of space-based humanitarian

assistance. They are cultivating the most accurate estimates of

soil moisture – the main determinant of crop yield changes – and

improving global forecasts of how well food will grow at a time

when the world is confronting shortages.

During a presentation this week at the the Joint Assembly of the

American Geophysical Union in Toronto, NASA scientist John

Bolten described a new modeling product that uses data from the

Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for EOS (AMSR-E) sensor

on NASA's Aqua satellite to improve the accuracy of West African

soil moisture. The group produced assessments of current soil

moisture conditions, or "nowcasts," and improved estimates by 5

percent over previous methods. Though seemingly small and

incremental, the increase can make a big difference in the

precision of crop forecasts, Bolten said.

The modeling innovation comes at a time when crop analysts at

agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) are

working to meet the food shortage problem head on. They combine

soil moisture estimates with weather trends to produce

up-to-date forecasts of crop harvests. Those estimates help

regional and national officials prepare for and prevent food

crises.

"The USDA's estimates of global crop yields are an objective,

timely benchmark of food availability and help drive

international commodity markets," said Bolten, a physical

scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

"But crop estimates are only as good as the observations

available to drive the models."

Crop analysts must estimate root-zone soil moisture, the amount

of water beneath the surface available for plants to absorb. But

estimating the amount of water in soil has posed challenges.

Ground-level sensors for rainfall and temperature -- the two key

elements for estimating soil moisture – are often sparsely

located in the developing nations that need them the most.

Hard-to-reach terrain like mountains or desert, lack of local

cooperation as well as high maintenance costs, can lead to

sensors more than 500 miles apart.

Under a new NASA-USDA collaboration known as the Global

Agriculture Monitoring Project, Bolten and colleagues from the

USDA's Agricultural Research Service are using AMSR-E to fill

the data gaps with daily soil moisture "snapshots." Since its

launch in 2002, the instrument has "seen" through clouds, and

light vegetation like crops and grasses to detect the amount of

soil moisture beneath Earth's surface.

AMSR-E uses varying frequencies to detect the amount of emitted

electromagnetic radiation from the Earth's surface. Within the

microwave spectrum, this radiation is closely related to the

amount of water that is in the soil, allowing researchers to

remotely sense the amount of water in the soil across any

geographic landscape.

Following a test of their system over the United States,

Bolten's team tracked West African rainfall, temperature, and

model assessments of soil moisture with and without the AMSR-E

satellite sensor observations. They used West Africa as a model

because the landscape provides varying cover, from desert and

semi-arid landscape in the north to grasslands, lush forests,

and crop land to the south. Rainfall in the region is highly

variable yet sparsely monitored by ground-based sensors. They

also targeted West Africa to demonstrate the possibility for

improving the assessment of drought-caused food shortages on the

region's dense population.

"Many developing countries are relying on limited and highly

variable water resources," said Bolten. "And typically those

same regions don't have adequate ground station data or

crop-estimating agencies capable of making reliable production

forecasts."

By definition, the severity of agricultural drought is

determined by root-zone soil water content. So Bolten's

satellite-driven boost to root-zone soil moisture prediction

also directly improves drought monitoring. And Bolten says

results from AMSR-E are just a precursor to dramatic new

improvements in data and prediction accuracy researchers expect

from the Soil Moisture Active and Passive satellite, slated to

launch in 2013.

Food reserves are at their lowest level in 30 years, according

to the United Nations World Food Program, putting the world's 1

billion poorest people most at risk. Prices for wheat, rice, and

corn have more than doubled in the last 24 months, hitting

countries like Haiti, Bangladesh, and Burkina Faso the hardest.

And the U.S. is not unaffected -- drought in 2008 led to an

estimated $1.1 billion in crop losses in Texas alone.

"This advance is making it possible for us to do our job in a

more precise way," said Curt Reynolds, a crop analyst for the

USDA's Foreign Agricultural Service in Washington. "We plan to

make NASA's soil moisture information available to commodity

markets, traders, agricultural producers, and policymakers

through our Crop Explorer Web site."

by Gretchen Cook-Anderson , NASA Earth Science News Team |

|