|

October, 2008

A

Bayer CropScience

editorial

|

Securing food with less land

Of the approximately 13 billion hectares of land

covering the Earth’s surface, around 1.5 billion

hectares are used for agriculture, with a

further 3.5 billion hectares being used for

meadowland and pasture. This area of land cannot

be increased. Every year, around seven million

hectares of agricultural land are lost as a

result of building construction, erosion,

desertification and other causes. Without modern

crop protection measures and fertilization, we

would already need significantly more arable

land, namely around four billion hectares. As a

result of population growth, agricultural

production must increase by around two percent

per year in order to be able to safeguard the

amount of food required to supply all people.

This figure does not yet take into account the

increases in demand for meat. In China, for

example, meat consumption has doubled in the

last 15 years. For one kilogram of beef, it is

necessary to produce well over seven kilograms

of animal feed – this also drives up the demand

for animal feed, which increases the competition

for arable land for food production.

|

|

|

|

|

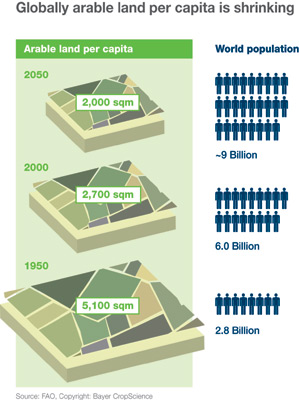

While the world population is rising year on year, the

arable land available worldwide remains practically the

same. This means that the per capita area available for

safeguarding the supply of food is constantly

decreasing. As a consequence, significant increases in

yields are needed to ensure that an adequate food supply

can be maintained in the future.

|

|

|

Stress reduces harvests

dramatically: cereals appear to suffer in particular

from abiotic stress caused by heat, cold, drought or

oxygen deficiency resulting from water stagnation or

compacted soil. Potentially record harvests (total

column length) are compromised partly by insect pests,

plant diseases and competition from weeds. Abiotic

factors are responsible for the lion’s share of harvest

losses, however.

|

Defying climate change

Our numbers are growing! By 2012, the world population is

forecast to top the seven billion mark. In 2025, the number of

people is even set to hit eight billion, with this rapid

population growth taking place almost exclusively in developing

countries, where over 80 percent of all people already live. And

it is precisely these countries that are already hit by food

shortages. The World Bank estimates that the number of hungry

people in the world could shoot up quite soon from 850 million

at present to 950 million. United Nations forecasts, meanwhile,

show that only 30 percent of the land that was available for

growing food in 1950 will be available per capita for

safeguarding the supply of food in 2050.

On top of this, worldwide food reserves have now dropped to

their lowest level for 30 years. The main problem is that there

is hardly any potential left for expanding the growing areas for

wheat, rice or millet. In many parts of Asia, every last hill

which can possibly be used has already been covered with fields

and rice terraces. In many regions of Africa, it is likewise

almost impossible to expand the amount of arable land. This is

partly because the soils are simply not suitable, and partly

because intensive farming would lead to desertification.

Extreme weather phenomena threaten harvests

Another problem is that meteorologists worldwide are registering

extreme weather events with increasing frequency – the absence

or displacement of tropical rainfall as well as abnormal ocean

current phenomena. One well known example is El Niño: every

three to six years, torrential rains devastate whole tracts of

land in South America, while at the same time extreme weather

leads to droughts in South East Africa, Indonesia and Australia,

and frost in Florida, causing enormous harvest losses for

farmers.

But it is not just natural catastrophes that cause billions of

dollars’ worth of agricultural damage each year: persistently

unfavorable farming conditions such as water shortages,

increasing salination of arable soils and extreme heat and cold

are prime causes of enormous harvest losses. Corn, rice and

wheat are no longer able to withstand the extreme environmental

effects. Climate change is adding to the stresses to which

plants are subjected, with grave effects; even with the best of

care for their fields, farmers regularly lose 30-70 percent of

their harvests.

Stop the self-destruction program in cereals

“There is an urgent need for us not only to make agricultural

production more efficient, but also to do it in a way which is

sustainable,” says Professor Friedrich Berschauer, Chairman of

the Board of Bayer CropScience. A key objective of the crop

protection scientists is to increase corn, rice and wheat yields

and make the plants more resistant to severe heat, cold, drought

or intense sunlight. These factors put plants under enormous

stress, triggering a process which can even lead to

self-destruction: the plant increases its energy consumption and

can therefore no longer produce certain energy transport

molecules, which are however needed by the cells to survive. The

supply gap has dramatic consequences for the plant, which can no

longer supply leaves, fruit or stems properly with energy.

Individual cells gradually die, followed ultimately by the whole

plant.

Stress-tolerant plants are considerably better at coping with

climate fluctuations

Researchers at Bayer Crop Science are using a trick to protect

rice plants, for example, against a number of stress factors.

They have put the plants on a fitness program. “Our idea was to

get crops into shape,” says Michael Metzlaff of the Bayer

CropScience Innovation Center for Plant Biotechnology in Ghent,

Belgium. To achieve this, his team is pursuing two strategies:

firstly, the scientists incorporate genes into the plants which

should help them deal with excessive stress caused by dry and

wet conditions. Secondly, they quite specifically deactivate

individual genes which trigger excessive stress reactions in

normal plants and lower the yield. “Our goal is to enable plants

to produce high, stable yields over the longer term in spite of

fluctuating environmental conditions," Metzlaff says.

A “second green revolution” is needed

For Berschauer, biotechnology is a vital tool to safeguard the

supply of food for the world population in the future. “We need

a second green revolution. If we use plant biotechnology in

combination with crop protection solutions in a targeted manner,

we can achieve significant advances in productivity,” comments

Bayer CropScience’s CEO. Other experts share this view:

according to the estimates of the Consultative Group on

International Agricultural Research, only with biotechnology can

harvests be increased by around 25 percent.

Antifungal agents help wheat plants to grow

In Canada, Bayer CropScience researchers are already using

advances in seed breeding to increase canola oil yields by up to

30 percent compared with conventional varieties. In addition to

plant biotechnology, new crop protection agents can also

increase harvest yields. The latest example is the active

ingredient trifloxystrobin. Farmers all over the world have been

using this agent for years to protect cereal, vegetable and

fruit crops against harmful fungal diseases. But

trifloxystrobin, an antifungal agent belonging to the

strobilurin group of active ingredients, can do more: it also

increases the ability of plants to withstand stress. “Field

trials show that crops in which strobilurins are used produce

better harvests than those protected with other types of

antifungal agent,” says Dr. Dirk Ebbinghaus, a Bayer CropScience

research scientist. Crops protected with trifloxystrobin also do

much better than untreated plants under conditions of drought.

“Our active ingredient clearly triggers a number of different

positive effects in the plant which result in an above-average

increase in yield,” says Ebbinghaus. The latest research results

have also shown that certain active ingredients, i.e. the Bayer

CropScience insecticide Gaucho®, can even make rice plants more

resistant to fluctuations in the salt content of water.

Protecting biodiversity

Because the demand for high-quality food in adequate quantities

and at affordable prices must not be allowed to jeopardize

nature, Bayer Crop Science has committed itself to an important

principle: using state-of-the-art technologies, the company

wants to help both small and large-scale farmers achieve higher

productivity on land already used for agriculture. This protects

natural habitats from being converted into arable land. |

|