Patancheru,

Andhra Pradesh, India Patancheru,

Andhra Pradesh, India

November 1, 2006

What ICRISAT Thinks...

by Dr. William D. Dar

Director General

International

Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)

Most scientists now agree that

global warming is inevitable, and that it will have major

impacts on climates worldwide. It will take a long time to

reverse this trend, and in the meantime adverse impacts on the

poor in developing countries will be especially harsh. We must

help them.

The poor can also help us, because they have been there before.

Dryland inhabitants have always been adjusting to large

variations in climate, both short and long-term. By looking

back, we will find clues to our future.

We also view current climatic

variability as a learning opportunity — in a sense, as a dress

rehearsal for future climate change. By helping the dryland poor

to cope better with current climate variability, we help them

better prepare for the future.

|

|

Squall lines that

bring unpredictable deluges to the West African

drylands are the embryos of the Atlantic

hurricanes that later hit the Caribbean and

North America |

|

What farmers think

At ICRISAT we are learning from

poor land-users through village-level socio-economic studies,

land-use surveys, and ‘farmer field schools.’ We also involve

farmers in our plant breeding research to learn about the plant

traits that they value most.

Villagers in India and in Southern/Eastern Africa, for example

tell us they have noticed changes in the amount and irregular

timing of rainfall in the past 30 years; whereas rainfall has

been slowly increasing in Africa’s Sahel region over the past

two decades (interspersed by punishing droughts). In all three

regions farmers have adjusted cropping practices and the

varieties of crops that they grow. We should work with them to

build on their solutions.

More from more

|

|

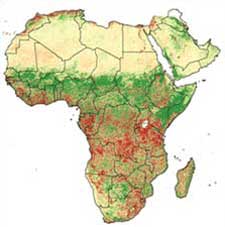

Satellite data

illustrate changing vegetation trends across

Africa, especially the re-greening of the Sahel

since the mid-1980s. Green: increasing

vegetation; red: decreasing vegetation*

|

|

We must help farmers prepare not

only for risks, but also for opportunities. Climate prediction

models do not yet tell us with great certainty whether rainfall

will increase or decrease in many dryland areas, or between

seasons. Higher rainfall and in some areas warmer temperatures

could even enable increases in agricultural productivity, but

may also bring diseases, pests and invasive species.

To help farmers get a better handle on these uncertainties,

we’ve partnered with meteorological services and leading climate

modeling researchers worldwide. We blend their knowledge with

our expertise on tropical dryland farming systems using

climate-driven risk analysis. This involves the use of

leading-edge tools such as weather-driven crop simulation

models, spatial weather data generators, and seasonal climate

forecasting models.

|

|

Nitrogen

fertilizer is essential to boost yields, but can

be risky in unpredictable climates because it

stimulates plants to use more water.

Computerized crop growth models combined with

weather data allow scientists to quantify this

risk vs. reward.** |

|

We should also seek opportunities

to make better use of natural resource assets, pools and flows.

Take water, for example. Much of the rain that falls on the

drylands, paradoxically, is ‘wasted’ from a farming point of

view—water that is never picked up by plants because it comes in

flood surges, or because soils are surface-sealed and unable to

absorb it, or because crop roots are underdeveloped due to

malnutrition and thus unable to take up the water efficiently

from the soil. We are helping farmers devise ways to manage

landscapes, soils and crops so that more of the water and

nutrient resources are stored and used more efficiently and over

a longer time period. This will prepare farm families to better

endure the greater variability of rainfall that many expect in

the future.

Likewise, we can get more from more by improving economic and

social resource assets, pools and flows. Co-learning with

farmers and research on how they innovate helps build social and

knowledge capital, and extends their benefits more widely. These

studies help us improve institutions and cooperation mechanisms

such as community self-help and joint credit associations,

micro-credit from socially-conscious lenders, market

opportunities that diversify risk, and affordable insurance

against severe drought. These increase farmers’ resilience in

the face of both current climate variability and future climate

change.

|

|

Breeders identify

hardy millet varieties that can resist extreme

stress conditions. |

|

Learning from genes

Farmers have also been astute in their development and use of

special breeds of livestock, crops and trees that are

genetically engraved with astonishing adaptive traits, many of

which we are yet to decipher.

They know that different plants

vary for soil fertility requirements and tolerance to flooding,

heat, insects and diseases, pressures that are all likely to be

affected by climate change. Natural and farmer-aided selection

have favored the evolution of remarkable traits such as

‘photoperiod sensitivity’, which ensures that the plants mature

around the same calendar date each year regardless of planting

date. This trait is valuable because farmers can only plant

after the rains begin in earnest — a date that is unpredictable

and varies widely from year to year.

Farmers insist on planting mixtures of genetically-different

plants and varieties because they know that if a stress knocks

out one genetic type, another is likely to survive it. They take

this even further: they not only diversify varieties within

crops, but they also grow a range of different crops, including

trees that disrupt winds and moderate the baking heat and

pounding storms that will increasingly punish crops as climate

change kicks in.

|

|

ICRISAT helped

farmers in the poor village of Powerguda become

the first in India to sell carbon credits (147

tons of carbon worth US$645). The credits,

bought by the World Bank, were earned by growing

Pongamia trees that store extra carbon while

yielding bio-diesel, yet another additional

income source. |

|

There is a lesson here for our

mono-cultured world. We have been narrowing genetic diversity to

fit our industrial agriculture over the last hundred years. We

need to do a better job of protecting and utilizing our

dwindling biodiversity assets, because with climate change on

the way we will need them more than ever.

We are carrying this lesson forward to help farmers expand their

agro-biodiversity and marketing options. By increasing the

number of high-value crops, trees, shrubs, and herbs available

for cultivation, and by growing them together in more diverse

farming systems, farmers will be less vulnerable to climatic and

economic shocks.

Together we can

To magnify our capacities and increase momentum on the crucial

topic of climate variability, we are building a coalition with

the Soil-Water Management Network of the Association for

Strengthening Agricultural Research in East and Central Africa

(ASARECA) and 15 national, regional and international

organizations. This consortium is endorsed by the New

Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and its

Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Plan (CAADP).

|

|

Farmers in the

Sahel protect trees such as Faidherbia

albida that tap deep water tables to provide

shade and dry-season fodder for livestock,

which in turn produce manure that improves

crop production. Trees also moderate the

land surface micro-climate and reduce wind

erosion. |

|

Investors have a key role to play

too, because they make our work possible. Some say we owe it to

the poor—after all, they are not the ones causing climate

change. But they are helping us find solutions. Through

increased investment and the use of modern scientific tools we

can accelerate the pace and scope of research —helping the poor

not only to survive, but to thrive.

by William D. Dar

Director General, International

Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)

*Vegetation changes may reflect

human activities as well as climatic variations. Data are

differences between the periods 1985-1992 and 1996-2003 for

averaged normalized difference vegetation indices (NDVI).

Source: data processed by ICRISAT from the Global Inventory

Modeling and Mapping Studies (GIMMS), University of Maryland.

** A simulation model (APSIM) was used to predict how maize

would respond to fertilizer in a drought-prone,

variable-rainfall area of Zimbabwe (Masvingo), using rainfall

data from a 46-year period (1952-98). The model found that

farmers were highly likely to enjoy a positive return on

investment in nearly all years, gaining a 10-fold return in

about half of the years when using micro-doses of just 17kg

N/ha, exceeding the financial returns obtained from the

conventionally recommended rate of 52kg/ha. These results have

given confidence to researchers, extensionists and fertilizer

enterprises to test micro-dosing with 200,000 dryland farmers in

recent years. |