Washington, DC

March 10, 2005

In addition to providing physical support and

taking in nutrients, plant roots secrete a wide variety of

compounds that affect other nearby roots, as well as insects and

microbes. But because it goes on unseen, bactericidal root

activity has not been extensively investigated—until now. Using

the model plant

Arabidopsis thaliana, a relative of garden-variety

cabbage, Jorge Vivanco and co-workers at Colorado State

University, together with Frederick Ausubel at Harvard Medical

School, demonstrated that “root exudates” contain antimicrobial

agents that ward off the continual attacks by soil pathogens.

The work is

published in the March 10 issue of the journal

Nature.

|

The

exudates from

Arabidopsis roots kill a wide range of

bacteria, confirming that roots are not always

vulnerable, anchored targets. The natural production of

these antimicrobial chemicals offers one explanation for

why so few bacteria types actually cause disease in

plants. Of the more than 50,000 plant diseases occurring

in the United States, fungal pathogens are the leading

cause.

“Current understanding of plant defenses does not

readily explain why a pathogen can cause disease in one

plant species and not another,” says Vivanco. “Our

findings will help researchers solve the mysteries of

plant disease and immunity.”

In

these experiments, however, root exudates did not kill

all of the tested strains of bacteria. One particular

strain of

Pseudomonas syringae, a bacterium that

causes disease in both tomatoes and

Arabidopsis,

has a seemingly fail-safe mechanism to overcome the

plant’s defenses. The bacterium not only survives

exposure to the antimicrobial substances, it also

blocks the plant's ability to produce them.

Both Vivanco and Ausubel are supported by separate

awards from the division of Molecular and Cellular

Biosciences at

The National Science

Foundation

(NSF). |

|

|

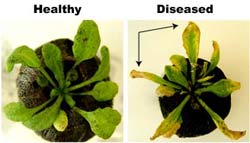

Plants, including the Arabidopsis thaliana shown

here, secrete antimicrobial compounds from their roots

as part of their defense against potential pathogens.

The plant on the left remains healthy after exposure to

the bacterium Pseudomonas syringae. In contrast, the

plant on the right was exposed to a strain of

Pseudomonas syringae resistant to the antimicrobial

compounds. Arrows highlight the signs of disease.

Credit: Jorge Vivanco,

Colorado State University |

Vivanco is

a recipient of NSF’s prestigious Faculty Early Career

Development Award (CAREER). CAREER awards support the early

career development of those researcher-educators who are deemed

most likely to become the academic leaders of the 21st

century. Parag Chitnis, the NSF program manager of Vivanco’s

award said, “This work is an exciting outcome of a bold and

challenging project. The work paves the way to understand and

combat crop diseases.”

The program

manager for Ausubel’s award, Michael Mishkind said, “The puzzle

of why so few bacterial species are pathogens remains a

fascinating problem. The simple, yet elegant experimental

approaches used by this team uncovered a critical aspect of the

battle that occurs between plants and microbes.”

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent

federal agency that supports fundamental research and education

across all fields of science and engineering, with an annual

budget of nearly $5.47 billion. NSF funds reach all 50 states

through grants to nearly 2,000 universities and institutions.

Each year, NSF receives about 40,000 competitive requests for

funding, and makes about 11,000 new funding awards. The NSF also

awards over $200 million in professional and service contracts

yearly. |